TGG and the American Dream – Paper 1: Unit 1

In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s iconic novel “The Great Gatsby,” the pursuit of the American Dream is a central theme that profoundly influences the actions and motivations of its complex characters. The definition of the American Dream is “The belief that America offers the opportunity to everyone of a good and successful life achieved through hard work.” (Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries) The American Dream, characterized by the aspiration for wealth, success, and social class, is portrayed as both a powerful motivator that drives individuals to strive for greatness and a source of deep disillusionment when the reality of their pursuits falls short. Disillusionment can be created through the ambition of the American Dream.

Jay Gatsby’s American Dream is centered around his desire to recapture the past and win back the love of his life Daisy Buchanan. Gatsby chases the American Dream through his relentless pursuit of wealth and status. It is through his questionable business, his parties, and his will to reclaim his lost love, Daisy. The extravagant parties display Gatsby’s wealth and his intention to get Daisy’s attention also elevating his status which are key elements to achieving the American Dream. He wanted a life that in the past he could not have with Daisy; “Gatsby did not want to be the same poor boy his entire life, so he dreamed up his lavish lifestyle and made it happen.” (Ava, Mural Chapter 6) Through his ambition, Gatsby did achieve partly what the American Dream consists of. He had gotten the Lavish lifestyle and the money though he had not achieved his love for Daisy.

Gatsby had experienced disillusionment during his pursuit of the American Dream. Realizing that Wealth and status cannot bring him true happiness or love he had silently suffered from loneliness masking it by the lavishing parties. Gatsby was obsessed with reclaiming Daisy and his past with her, despite her shallowness, which shows how he was misguided by the belief in the personal fulfillment of the American Dream. ‘“They’re such beautiful shirts,” she sobbed, her voice muffled in the thick folds. “It makes me sad because I’ve never seen such—such beautiful shirts before.”’(Daisy chapter 5) this shows how Daisy is when it comes to materialistic items, and also shows Gatsby how shallow she can be. In the end, Gatsby gets killed by George Wilson, due to Daisy’s accident. Which in turn symbolizes the corrupt nature of trying to achieve the American Dream. Where the pursuit of Wealth and status lends to ruin rather than true happiness.

Daisy Buchanan’s American Dream revolves around wealth, social status, and security. Daisy strives for a life of comfort and luxury, which is why she marries Tom Buchanan, who can provide her with the financial stability and social standing she craves. Daisy’s lavish lifestyle is apparent in her house, the parties she attends, social status of people she knows. We see throughout the novel that Daisy has a very lavish lifestyle. We first see it in chapter one when Nick goes to see Daisy at her house. “a cheerful red-and-white Georgian Colonial mansion, overlooking the bay,” (chapter 1) Nick sees Daisy lounging in a white dress drinking in a very large house with no care for whoever sees her. However, while Daisy achieves these symbols of success, her emotional and mental capacities are hard to understand. Suggesting that all the American dream is made out to be may not be as fulfilling as it seems.

We see Daisy become disillusioned as a result of not having the full American dream, realizing that the pursuit of wealth and status fails to bring her true happiness and emotional fulfillment. Despite her luxurious lifestyle and status, Daisy’s life is ruined by the lack of love and connection, particularly in her marriage to Tom Buchanan. Her moments of slight happiness with Gatsby “At his lips’ touch she blossomed for like a flower” (Chapter 5) highlighting the emptiness of her material success. However, she ultimately chooses the security of her success with Tom over emotional fulfillment and happiness with Gatsby. This disillusionment highlights the hollowness of the American Dream, revealing again that wealth and status leave people with desires unfulfilled.

Nick’s American Dream is focused on personal growth. The American Dream is sought out throughout the novel, though Nick searches for it by moving to West Egg to make a fortune in business. He rents one of the smaller houses that is alongside some mansions, which allows him to observe and interact with the wealthy Jay Gatsby. This proximity to wealth and his professional success embodies the traditional aspect of the American Dream, as Nick aspires to be financially stable with social connections. “ I was privy to the secret life of the rich.” (chapter 1) This shows that Nick would observe Gatsby for his gain. Through watching and talking to Gatsby Nick finds ways he can get ahead in life with the help of Gatsby.

When Nick learns that pursuing wealth and status frequently results in moral decay and emptiness, he loses faith in the American Dream. Nick becomes increasingly disillusioned with the American Dream as he observes the moral decay and superficiality of the wealthy elite living in West Egg. His experience is marked by witnessing Tom Buchanan’s blatant infidelity and arrogance, this happens when Nick sees how Tom is towards Daisy and when he is with his lover, Myrtle. Additionally, he sees Daisy’s shallow pursuit of wealth over genuine love, which emphasizes the lack of happiness in their lives. These experiences collectively reveal to Nick the hollowness and corruption of the lives of those who have achieved the American Dream, exposing the contrast between illusion and reality. However, Nick’s initial admiration for their glamorous lifestyle begins to fade, transforming into disillusionment that makes him not want that lifestyle.

The American Dream undoubtedly drives ambition and motivates individuals to strive for greatness, but it also creates a sense of disillusionment among many. Through the complex relationships and experiences of characters like Gatsby, Daisy, and Nick, we gain a deeper understanding of how the American Dream is ultimately just that—a dream. It is an ideal that some can achieve but at what cost to their integrity, relationships, and mental well-being? The pursuit of this elusive dream often leads to sacrifice and heartache, raising important questions about its true value and impact on people’s lives.

The Great Gatsby vs. The Chosen and The Beautiful – Paper 2: Unit 2

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Chosen and The Beautiful by Nghi Vo are both set in the vibrant and transformative decade of the 1920s, a period marked by significant social change and cultural upheaval. One narrative unfolds through the eyes of a white male named Nick Carraway, whose perspective offers a particular lens on the events and characters around him. In contrast, The Chosen and The Beautiful is narrated by an Asian woman, providing a distinct viewpoint that enriches the narrative. Both novels intricately explore themes of identity, privilege, and societal expectations, specifically focusing on the intersections of gender, race, and sexuality. Through their unique voices and experiences, these works illuminate the complexities of life during this era, revealing how different identities shape one’s understanding of race, gender, and sexuality.

In The Great Gatsby, Nick Carraway’s narrative perspective offers a distinctive and critical viewpoint on the gender roles prevalent during the 1920s. Through his observations, Nick shines a light on the restrictive societal norms and expectations imposed on both men and women in that era’s culture. He illustrates how these gender roles shape personal identities and relationships. For instance, Daisy Buchanan finds herself trapped in a shallow and emotionally unfulfilling marriage, where she is expected to maintain a facade of happiness, despite her underlying dissatisfaction. “I couldn’t forgive him or like him, but I saw that what he had done was, to him, entirely justified. It was all very careless and confusing. They were careless people, Tom and Daisy, they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.” (Nick chapter 9) This situation reflects the immense social pressures placed on women to conform to specific standards of femininity, often at the expense of their desires and individuality. Conversely, Nick portrays Daisy’s husband, Tom Buchanan, as the embodiment of toxic masculinity, characterized by aggression, entitlement, and a blatant disregard for the feelings of others. These quotes that Nick is describing how Tom is portrayed “two shining arrogant eyes,” “a rather hard mouth,” and “a body capable of enormous leverage, a cruel body,” shows how most men held themselves in the 1920s. This portrayal serves to highlight the rigid gender norms of the 1920s and the struggles individuals faced as they navigated their prescribed social roles. Nick’s reflections not only emphasize the limitations imposed on both genders but also provoke a deeper understanding of the emotion that arises from such constraints, ultimately shedding light on the broader implications of these societal expectations in shaping personal relationships and identities during this decade.

Jordan Baker, the narrator of “The Chosen and the Beautiful,” is portrayed as an Asian adoptee who is queer, whose distinct viewpoint questions and subverts the gender conventions that were common in the 1920s. Readers are given the opportunity to see the different limitations society imposes on women through Jordan’s perspective, as well as the flexibility of gender in a society where strict social norms and expectations rule. For example, Daisy must maintain a particular appearance or role or else everyone will not like her. For instance, Daisy is extremely distressed by a letter from her ex-lover, Gatsby, when she is scheduled to eat dinner with some family prior to getting married. She asks Jordan to create a “new her” so she can go to dinner with the family because she looks awful after that. Nghi Vo challenges the constraints imposed by cultural gender norms and highlights the intricacies of identity by providing a voice to a marginalized character like Jordan, ultimately highlighting the complexity of human existence. This method challenges readers to reevaluate how they define themselves and to acknowledge the wide range of experiences that go beyond accepted standards.

Through Nick’s point of view, we gain a vivid insight into the racial attitudes and prejudices that were pervasive in the 1920s. The casual racism that characterized the era’s society is depicted through various interactions and dialogues. Tom Buchanan’s overtly racist comments, which assert the superiority of the white race and express his apprehension about racial mixing, serve as a striking reflection of the white supremacy that was widely accepted at the time. Although Nick is less openly biased than Tom, he does not question these deeply ingrained beliefs, suggesting a tacit acceptance of the existing racial hierarchies that governed social interactions. Furthermore, Nick’s description of people of color, such as referring to the “modish negroes” in their chauffeur-driven vehicles, illustrates his passive approach and highlights a troubling tendency to perpetuate stereotypes. This choice of words reveals a complicity in the normalization of racism, as Nick presents these views without overt criticism. His narrative effectively illuminates the racial dynamics that underlie the relationships between the characters and the broader structures of society. Through Nick’s observations, readers are confronted with an unsettling mirror of the era’s attitudes, prompting reflections on how these prejudices shaped not only individual lives but also the very fabric of social interaction during the 1920s.

Jordan’s narration profoundly influences the exploration of race, offering a fresh and critical perspective on the racial dynamics of the 1920s. The narratiors experiences and observations shed light on the racial prejudices and exoticism faced by non-white individuals in a predominantly white society. Through Jordan’s narrative, Vo delves into the complexities of identity and belonging, illustrating how race intersects with other social categories. An example of this is when Tom talks about the Rise of the Colored Empires book he read. In bringing this book up he says “It’s up to us, who are the dominant race, to watch out or these other races will have control of things.” Showing that Tom is openly racist even infront of Jordan, an Asian woman. This unique narrative perspective allows the novel to critique the racial inequalities of the time, revealing the often-overlooked struggles of marginalized communities. By centering the story on a character who navigates multiple layers of otherness, the novel challenges the dominant racial narratives and underscores the importance of diverse voices in literature. Jordan’s interactions with other characters reveal the complexities of allyship and complicity within friendships and romantic relationships, further enriching the narrative. Such as her response to Tom’s racism. She says “Youve got to beat us down” in a sarcastic way in showing that even though she’s wealthy doesnt mean she’s not who she is. By weaving together personal anecdotes and broader social commentary, the novel not only captures the essence of the 1920s but also resonates with contemporary discussions surrounding race, identity, and intersectionality, making it a vital contribution to modern literature.

An examination of 1920s views on sexuality can be found in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s seminal work, The Great Gatsby. Through the experiences and observations of Nick Carraway, the novel exposes the complicated and even incongruous attitudes of the time regarding sexual relationships. Daisy Buchanan’s brief romance with Jay Gatsby, along with Tom Buchanan’s and Myrtle Wilson’s extramarital affairs, reveal a society that simultaneously celebrates and condemns sexual freedom. This duality reflects the era’s shifting values, as the Jazz Age brought about new possibilities for personal expression but also clung to the remnants of Victorian morality. Nick himself appears to waver between moral censure and curiosity, mirroring the larger cultural conflict between traditional values and the quest for pleasure. His ambivalence is palpable as he navigates through the opulence of Gatsby’s world, which often blurs the lines of appropriate conduct. Nick’s description of the lavish gatherings at Gatsby’s estate, where the boundaries of decency and excess are regularly tested, further demonstrates this societal skepticism. Through these vivid scenes, Fitzgerald reveals the underlying hypocrisy and double standards of the times, where sexual liberty is both praised and denounced in equal measure. Readers gain insight into the intricacies of sexual norms and the tensions they create in the lives of individuals, illustrating how personal relationships are influenced by the broader cultural landscape. From Nick’s perspective, the complexities of desire and morality are laid bare, allowing for a deeper understanding of the struggles faced by characters caught in the throes of a rapidly changing society.

Narrated by Jordan Baker, a queer character, the story provides an intimate look at the varied expressions of desire and love that defy the heteronormative standards of the 1920s. Jordan’s perspective as a bisexual woman allows the novel to explore the intersections of sexuality with race and gender, highlighting how societal norms restrict and define personal identity. Through her experiences and relationships, Vo challenges the rigid sexual mores of the time, presenting a world where love and attraction are multifaceted and not confined by traditional boundaries. Jordan’s narrative is filled with moments that reveal the complexities of her relationships, offering insight into the emotional landscapes of those who dare to love outside societal expectations. Through Jordan’s narration, she also seems to struggle with the fact that Nick, Jordan’s lover, is in love with Jay Gatsby. Having this introduced throughout the story, we are given more insight into the different struggles of her sexuality and relationships. By showcasing the struggles and triumphs of characters who navigate their identities in a repressive society. Jordan’s voice becomes a beacon of hope and authenticity in a world yearning for greater understanding and inclusivity.

The Great Gatsby and The Chosen and the Beautiful and two novels set in the time frame, that are the same novels though have two completely different narrations. So through their distinct voices and experiences, these pieces provide light on the intricacies of life in this time period, demonstrating how one’s perception of race, gender, and sexuality is shaped by many identities.

Adaptations of the Great Gatsby – paper 3: Research Paper

Audiences have been captivated by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby for many years due to its detailed depiction of the Jazz Age and the pursuit of the American Dream. Numerous film adaptations have emerged from the themes and abundant symbolism of the novel, each one presenting Fitzgerald’s work through unique cultural perspectives and cinematic approaches. The numerous adaptations serve as representations of distinct artistic visions while simultaneously addressing widespread societal concerns, including materialism, class divisions, and identity formation.

The scholarly work of Irene Kahn Atkins draws attention to the multifaceted difficulties encountered by filmmakers attempting to depict Gatsby’s world, where cinematic adaptations struggle to maintain allegiance to the original text while simultaneously engaging modern audiences (Atkins, 1974). Frank R. Cunningham delves deeper into this tension by examining the inherent challenges faced when translating literary subtleties into visual narratives, highlighting adaptation as a creative reinvention process instead of mere replication (Cunningham, 2000). The cultural elements depicted in both the novel and film serve as mediums through which evolving Jazz Age perspectives on race, gender roles, and dominant values are examined—recent critics such as Vella (2024) study these portrayals to understand how they influence audience perceptions. The examination of various cinematic versions reveals how thematic focus and stylistic elements evolve to reflect their distinct historical periods. Through the examination of the 1974 and 2013 versions side by side, researchers reveal how filmmakers employ the setting along with narrative methods and symbolic elements to present Gatsby’s tragic quest within various artistic patterns. The intricate discussions presented in this study demonstrate how The Great Gatsby remains a pertinent focal point where literary analysis converges with film studies and cultural critique.

The examination of cinematic versions of The Great Gatsby has persistently attracted scholarly attention because these adaptations illustrate the inherent difficulties filmmakers face when attempting to transfer Fitzgerald’s intricate storytelling and multifaceted characters into a visual medium. Numerous film adaptations since the novel’s 1925 release have strived to embody its core elements while reflecting the distinct cultural and artistic influences of their respective periods. The 1926 silent film directed by Herbert Brenon represents an early adaptation that encountered technological limitations yet attempted to portray Gatsby’s confusing character through visual symbolism and expressive acting techniques. Irene Kahn Atkins examines the initial attempts to adapt Fitzgerald’s work, which faced challenges in maintaining his literary style while they frequently reduced plot elements to appeal to modern viewers (Atkins 216). The evolution from silent films to talking opened new avenues for dialogue-driven character development while simultaneously provoking inquiries regarding the preservation of literary skill.

The 1974 cinematic version under Jack Clayton’s direction undergoes frequent scholarly examination due to its efforts to achieve period authenticity while remaining faithful to Fitzgerald’s original work. Frank R. Cunningham observes that the film gains strength from its talented cast and luxurious production elements, yet struggles with pacing problems alongside a too literal approach, which occasionally reduces its thematic complexity (Cunningham 187). The cinematic work in question emerges from a period when directors focused on meticulous authenticity, which led to a depiction that numerous critics perceived as emotionally detached.

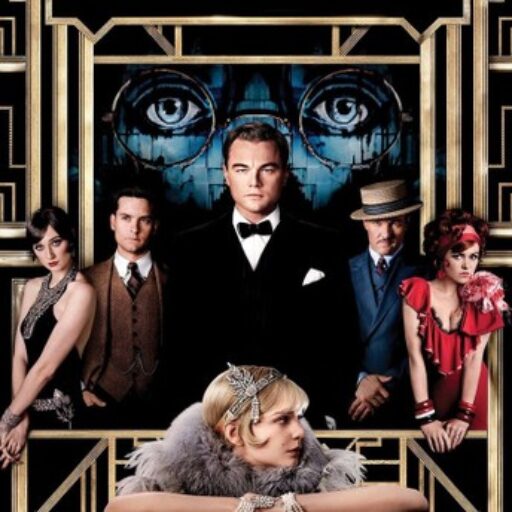

The most contemporary adaptations exhibit an increased level of stylistic experimentation. The 2013 cinematic work by Baz Luhrmann represents this movement through its fusion of modern musical elements with lavish visual presentation to connect with today’s audience while maintaining the essential motifs of extravagance and disenchantment. The manner in which Louis Giannetti examines Baz Luhrmann’s cinematic technique shows how it breathes new life into Gatsby for contemporary viewers while simultaneously creating division among audiences through its exaggerated theatrical elements (Giannetti). The current iteration emphasizes persistent discussions regarding the equilibrium between maintaining authenticity and exercising artistic freedom in literary adaptations.

The collective body of Great Gatsby film adaptations demonstrates how filmmakers have developed and changed their techniques to connect with Fitzgerald’s literary masterpiece. Every iterative process of adaptation engages in a negotiation between maintaining textual fidelity and pursuing artistic reinterpretation, which mirrors the wider debates within adaptation studies about the balance between authenticity and creative innovation. Through their collective efforts these films establish The Great Gatsby‘s lasting cultural impact by persistently redefining its story across various historical periods.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald stands as an intricate literary work that enables a detailed examination of 1920s American cultural depictions through its exploration of the conflicts between established high society and emergent wealth, alongside themes of the American Dream and social hierarchy. Through its portrayal of the Jazz Age, the novel captures both the period’s vibrant energy and ethical uncertainty while simultaneously mirroring widespread societal fears concerning swift technological progress and evolving social norms. Gatsby himself embodies this cultural paradox: The figure of Gatsby stands as a representation of contradictory cultural elements where his extravagant wealth exhibitions serve as symbols for both the opportunities and dangers associated with social advancement within capitalist structures. The extravagant gatherings he hosts serve as tiny worlds that exemplify a society fixated on grand displays while simultaneously entrenched in shallow interactions and feelings of disconnection.

Through the intricate dynamics between characters, the narrative exposes deeply rooted class barriers, which serve as a critical examination of the equal opportunity that defines American identity. Tom Buchanan stands as a symbol of inherited wealth who sustains his social supremacy by wielding economic influence alongside racial superiority beliefs, which serve to highlight Fitzgerald’s examination of exclusionary race and class dialogues from his time. Daisy Buchanan stands as the embodiment of the elusive idealization connected to wealth and social standing; her character demonstrates how cultural ideals become enmeshed with materialism and emotional detachment.

Fitzgerald employs the setting as a symbolic mechanism to define cultural distinction, where East Egg stands for an entrenched aristocratic society and West Egg embodies the aspirations of newly wealthy individuals. The geographical division serves as a representation of deeply rooted societal conflicts within America about what constitutes genuine personal achievement versus manufactured success. The Valley of Ashes presents an additional layer of complexity to these representations through its manifestation of industrial decay and moral desolation that lurk beneath apparent surface opulence. Cinematic versions of literary works frequently struggle to represent intricate cultural aspects on film and tend to prioritize either glamorous elements or critical perspectives (Atkins 216). The interpretations presented here demonstrate how societal views about the 1920s ethos have changed across various historical periods. The Great Gatsby stands as a powerful cultural artifact that examines its historical period while simultaneously engaging with persistent American cultural discussions about identity, aspiration, and social inequality.

A thorough examination of critical perspectives regarding Gatsby films uncovers an intricate conversation that balances adherence to the original text with the creative freedoms that filmmakers exercise during cinematic adaptation. Academic authorities, including Irene Kahn Atkins, assert that translating Fitzgerald’s intricate narrative voice and thematic skill into film presents significant challenges because cinematic adaptations tend to focus on visual spectacle at the expense of literary depth (Atkins 216). The tension becomes apparent through adaptations that emphasize lavishness and excess yet frequently overlook the novel’s critical examination of how the American Dream becomes corrupted. Frank R. Cunningham expands his examination of this topic by discussing what he defines as “the problem of film adaptation,” which presents filmmakers with the challenge of balancing the preservation of authorial intent against the need to attract modern viewers (Cunningham 187). Cunningham proposes that every adaptation serves as a reflection of both Fitzgerald’s original work and the specific cultural context during which it was produced, leading to diverse interpretations that simultaneously reveal and hide essential elements of the novel.

Louis Giannetti examines specific adaptations that simplify characters, including Gatsby, by portraying him as just a romantic figure, thus stripping away his complex moral ambiguity (“The Gatsby Flap”). How these portrayals are presented threatens to undermine Fitzgerald’s intricate examination of how individuals construct their identities while engaging in self-deception. A number of critics have observed that certain films prioritize romantic melodrama, which diminishes their social critique and changes the novel’s ideological impact. Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 adaptation showcases a lavish visual style that represents this divide; it received acclaim for its dynamic energy and contemporary soundtrack but faced criticism for allowing spectacle to overshadow fine narrative elements. Some academics contend that these filmic selections create fresh avenues for interpretation by placing Gatsby into contemporary contexts, which maintain Fitzgerald’s work as pertinent for successive generations. The varying critical reception highlights an enduring discussion about whether strict adherence to literary sources should remain the ultimate goal or if adaptive transformation represents a legitimate artistic expression. The body of critical analysis regarding Gatsby film adaptations demonstrates a persistent conflict where filmmakers attempt to reconcile visual creativity with faithful textual representation—a fundamental difficulty inherent in translating intricate literary works into cinematic form.

Examinations of cinematic adaptations of The Great Gatsby demonstrate significant variations in stylistic approach as well as thematic focus and narrative attention, which mirror changing cultural environments and directors’ interpretations. Jack Clayton’s 1974 cinematic rendition stands as a hallmark of traditional interpretation, which showcases an unwavering commitment to Fitzgerald’s original work through meticulous replication of period details and dialogue. The tragic love story of Gatsby and Daisy takes center stage in this version through a controlled visual approach that mirrors 1920s social realism while highlighting the moral corruption hidden beneath the glamorous exterior (Atkins, 1974). Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 film version presents a distinctive and deliberately vintage visual style that combines modern musical elements with quick editing methods alongside lavish set designs. Through his cinematic approach, Baz Luhrmann amplifies the inherent spectacle of excess within Gatsby’s world while using symbolic elements such as vivid color palettes and dynamic camera work to explore themes of illusion versus reality (Moresca, 2022). This contemporary presentation manages to encapsulate both the captivating charm and the empty materialistic values that stand at the core of Fitzgerald’s critical examination.

The two films both address class grouping and the pursuit of the American Dream, yet employ markedly different representational techniques. The cinematic production from 1974 sustains a restrained tonal approach, which emphasizes character evolution through nuanced dialogue and performance, while Robert Redford’s portrayal of Gatsby reflects a wistful idealism restricted by social obstacles. Leonardo DiCaprio’s performance, directed by Luhrmann, exhibits a frenetic energy that embodies contemporary anxieties related to identity construction within consumer culture as discussed by Cunningham in 2000. In addition to his treatment of primary characters, Luhrmann deliberately enhances the flamboyant traits of secondary figures like Myrtle Wilson to underscore social ambition themes. The film adaptations under examination demonstrate divergent adaptation theories through their execution. Clayton’s work attempts to maintain narrative fidelity while potentially sacrificing cinematic fluidity, whereas Luhrmann integrates intertextual elements from Fitzgerald’s work with contemporary influences to achieve emotional impact for modern viewers (Atkins, 1974). Both cinematic interpretations of The Great Gatsby demonstrate its flexibility as a text by balancing historical accuracy with creative exploration. The examination of various adaptations reveals that Fitzgerald’s novel cannot be fully represented by any single version because each one emphasizes distinct aspects determined by its historical context and the director’s vision.

A detailed study of multiple The Great Gatsby film versions demonstrates the intricate challenges filmmakers face when attempting to transfer Fitzgerald’s subtle storytelling techniques and abundant symbolic elements into cinematic form. Every film adaptation of Gatsby’s tale presents unique interpretations that showcase the director’s artistic vision while simultaneously reflecting the cultural environment of its production period, therefore highlighting the story’s evolving nature through different eras. A detailed examination of cultural representations reveals that these adaptations transcend storytelling to address modern social issues and aesthetic movements, which in turn alters how audiences perceive concepts of identity, wealth, and the American Dream. The examination of critical perspectives on these films serves to illuminate the persistent debates surrounding fidelity to source material versus creative innovation while simultaneously highlighting the tensions that exist between literary purism and cinematic expression. The examination of various adaptations reveals that directorial decisions regarding casting, setting, and narrative focus serve to either amplify or diminish the thematic elements present in Fitzgerald’s work. These diverse adaptations encourage examination of defining authentic adaptation while film as a medium manages literary heritage and seeks to attract varied audiences. Through its comprehensive examination of The Great Gatsby adaptations, this study reveals how cinematic reinterpretations function as important cultural artifacts that simultaneously maintain and modify literary traditions. The interaction between written text and visual screen media expands our comprehension of Fitzgerald’s literature by positioning it within changing artistic methods and societal norms. Through intricate scholarly examination, The Great Gatsby emerges as a perpetually relevant platform that enables the exploration of American identity across both literary and cinematic domains.