My focus throughout the semester ended up being largely on audience interpretation. This works well with the theme of Gatsby in the 21st century, I believe, because there is much to be said about how a book is differently interpreted by readers 100 years later. Most of my blog posts ended up being very silly, despite my best efforts. It’s simply who I am! I don’t have much to say, and I’ve been attacked with an onslaught of migraines and sickness in this fabulous last week of the semester, so let’s go ahead with it.

Thank you endlessly for your support and feedback throughout the semester!

- Paper One

- Paper Two

- Paper Three

- Multimodal Project

- Final Bibliography

Paper One, “The Great Gatsby is a Question”

The Great Gatsby was released in 1924 to poor reception, but now, a century later, has

broad social relevance in America. Why? I posit that it failed originally for the same reason it

now stays in the public consciousness: its versatility. This will interest those who are already

invested in the conversation of what it is that makes TGG endure, but should also speak to those

who are interested in the value of media that does not spoon-feed its message to its viewers. The

characters of The Great Gatsby are, almost completely, just representations of their social

statuses. It is not a story about Myrtle, Daisy, Nick, Gatsby, and so on. It is a story about the

wealthy interacting with the poor, women interacting with men, and the educated interacting

with the uneducated. This makes it remarkably easy for almost any reader to relate, but at the

same time, makes Fitzgerald’s actual intention with the novel unclear.

Every narrative has its connections to the real world, of course. Stories are meant to be

applied to the reader’s life. What makes this worth mentioning in regards to The Great Gatsby is

how obvious it is with what its characters represent. It is easy to grasp onto how these characters

behave, because we are not introduced to them as people, but to where they stand in the world.

Particularly because we are seeing the world through Nick’s lens, and he notices people’s social

standing before their personality. Meeting the Wilsons is a good example. “The interior was

unprosperous and bare; the only car visible was the dust-covered wreck of a Ford which

crouched in a dim corner.” is the first thing we hear of George, only: it isn’t about him at all. It’s

a description of his living space, which we (the readers as well as Nick) use to make assumptions

about his character. And Myrtle, “She was in the middle thirties, and faintly stout, but she

carried her flesh sensuously as some women can.” She is introduced to us as being stout and

older, but carrying herself in a way that makes her attractive, much like how she gets away with

Tom to experience the nicer things, fancy dresses, expensive dogs, and high rise apartments,

despite herself living above the garage with Wilson in the valley of ashes. This doesn’t apply

with just the working class characters, either. We are introduced to Gatsby’s parties and wealth

far before we meet Gatsby himself, and one of the very first things Nick mentions about Tom is

how “His family (is) enormously wealthy”. Their purposes are clear from the get-go, because we

experience the story through Nick, who is only interested in getting to know them on a surface

level. Since we only see what Nick sees, though, that leaves us with characters we only know on

a surface level. Which is what makes them so easy for readers to project their ideas onto: they’re

essentially blank slates, with parameters loose enough to get the ball rolling.

That’s exactly the thing, The Great Gatsby is full of loosely defined concepts. That isn’t

to say I think they’re undeveloped. In fact, I believe this to be a careful choice by Fitzgerald. It

comes back to what many people believe the most interesting part of TGG is: Nick as a narrator.

He is unreliable, judgemental, and doesn’t make moves to engage with the story. For example, “I

believe that on the first night I went to Gatsby’s house I was one of the few guests who had

actually been invited. People were not invited—they went there.”, Nick was fully capable of

attending Gatsby’s parties without having been invited, yet did not until he was directly asked to

do so. He has a passive role in the story, and doesn’t actually do much except for tagging

alongside the more boisterous characters and planning Gatsby’s funeral. He is in fact also a bit

shy- not engaging in the party until he spots Jordan, then using her as a social “in”. This all

builds onto how the novel is kept relatively surface level, very much purposefully. In H.L.

Mencken’s review of TGG for The Chicago Tribune, he claims “Fitzgerald seems to be far more

interested in maintaining its suspense than in getting under the skins of its people.” I would argue

that this isn’t Fitzgerald’s interest, but Nick’s. A purposeful decision in his writing to keep us

distanced from the personal cores of these characters so that they can continue to serve as vessels

for Nick’s (and our) judgements. We are not meant to get under the character’s skins. And if

Mencken is referring to the readers when he says “its people”, then I feel it’s a bit ironic, because

it certainly seems to have gotten under his skin in his negative review, where he calls The Great

Gatsby “Obviously unimportant”.

In a letter to his editor, Fitzgerald wrote: “Of all the reviews, even the most enthusiastic,

not one had the slightest idea what the book was about.” So what is it about? Why write The

Great Gatsby? I can only tell you what I think. I believe The Great Gatsby is a criticism of,

conversation with, and observation on American society. Particularly in the 1920s, but honestly,

we haven’t changed all that much. Fitzgerald wanted to make his readers reflect upon

themselves. This is why the characters are so easy to project onto: they are being held up to us

like mirrors. He is asking us to take a look and see what we think. I don’t believe there’s a

definitive answer to what message TGG is supposed to deliver: that would imply it’s making a

statement, rather than asking a question. Is this why “even the most enthusiastic” reviews didn’t

understand what the book was about? Because it isn’t a story, really, but a commentary. You

would miss the point if you were looking for a narrative, if you were reading about Nick and

Daisy and Gatsby rather than about yourself and the world around you. Of course I could just be

another in the pile of people who don’t get it, and I probably am. Isn’t that what makes Gatsby so

compelling, though? That there are an infinite number of supposedly “wrong” takes, and we’ll

never know for certain what FSF intended. When a media is “answered” it fades out; what can

be extracted and learned from it, is, and we move on. This is why it’s important to put some faith

in the viewers. If you provide every answer already cut and dry, they have nothing to chew on, so

to speak. That is why it endures. That’s what makes any media stick. That they aren’t statements

with a definitive end, or puzzles with a single result, but a conversation that can be held and

argued far past their original lives.

Paper Two “Building On, Rather Than Destructing”

By changing the race, gender, or sexuality of a character, you are able to recontextualize their every action & thought. A Black or transgender character who feels a sense of alienation holds a different meaning than a White male character who feels the same, for example. The ousting of POC and Queer people in the real world provides context for this example character’s feeling of disbelonging. Those who experience real life discrimination will then see themselves represented in characters like them, encouraging them to connect and interact with the story in a way that they may not otherwise. This becomes especially important in the context of a novel as old as The Great Gatsby, where its endurance relies entirely on the audience, as there is no longer an author to advertise it.

In Self-Made Boys, Anna-Marie McLemore rewrites Nick as Nick Caraveo, a gay, Latino, transgender man. Though these changes from the original Nick’s implied status as a White cis man recontextualize his character and actively change the way he behaves, he keeps core traits such as his dedication to logic and cynicism, his self-consciousness, and his hesitancy to get involved that keep him recognizable as well as maintaining his role in the story as the cynical outsider. These traits are still reframed, though. Consider their shared hesitancy: where Nick Carraway doesn’t get involved in anything due to a self-perceived superiority to others, Nick Caraveo’s hesitancy stems more from a fear of losing his current position in life by getting involved with people who could ruin his career. In The Great Gatsby, Nick says this: “I believe that on the first night I went to Gatsby’s house I was one of the few guests who had actually been invited. People were not invited—they went there.” He is bragging about the fact that he did not attend until directly requested, setting himself apart from the regular attendees by declaring himself as a unique case. He is wanted at the party, unlike everyone else. This sense of superiority stems from his cynicism– he believes himself to have a unique viewpoint that makes him smarter than and places him above “the rest”. Nick Caraveo’s cynicism, on the other hand, comes more from a jaded view of the world that he has gained from being a poor beet farmer and a brown man in a world that does not make room for him to succeed. Caraveo writes in a letter to Daisy: “How many New York finance men do you think loiter around Beet Patch? If he hadn’t blown a tire, he never would have stopped.” If it weren’t for the coincidence of the New York finance man’s tire blowing where Nick lived, he would never have gotten the opportunity to work in New York. Even once he arrives, it is made very clear that it is a White man’s world, and Nick is given a shabby desk in a bad position in the office – even once he gains the opportunity, it is actively made difficult for him because he is not White. The opportunity fell in his lap the same as happens for Nick Carraway (He only gets to know Gatsby by the chance that he is related to Daisy), but Caraveo has to work to keep his position in a way that Carraway does not. This actually gives him a more solid motivation as a character- he has a good reason to stay away from the racist, white-supremecist Tom, for example, as well as a secondary reason (apart from knowing Tom is cheating and to make Jay happy) to want Daisy to break things off with Tom.

Daisy’s character is inextricably linked with her identity as a woman facing sexism and infantilization in 1920s America. It is an integral part of her characterization in both Self-Made Boys and The Great Gatsby. Self-Made Boys adds onto her characterization by writing her as a White-passing Latina and closeted lesbian. By adding these layers of context, we are given a more complex, complete picture of who Daisy is, rather than the broad strokes that are given to us in The Great Gatsby. Self-Made Boys has its own rendition of the famous beautiful little fools quote that encapsulates the similarities and differences between the two Daisys well.

In The Great Gatsby: “I’m glad it’s a girl. And I hope she’ll be a fool—that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool.”

Compared to: “Men love beautiful, useless, expensive things. So I’m meant to be one. I’m not supposed to be any- thing but a beautiful little fool.” in Self-Made Boys.

There is context added to Daisy feeling objectified when we take into consideration that she is Latina. There is a real life problem of Latinas being sought after for the stereotype of being “feisty” or “exotic” women, which is a form of objectification that stems from racism. While Tom believes she is White, it is entirely possible she has faced this issue previously, or that she will face it in the future. There is also the bigoted belief that women of color are less intelligent, compounded with the way women in general were treated as frivolous and airheaded in the 1920s. Women are not expected to be capable of anything as they are believed to be too emotional and frail, and a large part of Daisy’s intrigue as a character comes from how she plays into this belief in order to benefit her lifestyle, disregarding her inner conflict with it. Self-Made Boys continues this theme rather than overwriting it– in the same way Daisy Buchanan realizes her life would be easier if she was stupid, so she pretends to be stupid, Daisy Fabrego realizes her life would be easier if she was White, so she pretends to be white. In both cases, she only perpetuates the issues by leaning into them and causes herself distress, but does succeed in achieving a wealthy, worry-free external lifestyle. You can begin to see a theme here. Self-Made Boys uses the changes in the character’s races to further expand upon the already existing themes and characterization found in The Great Gatsby.

Anna-Marie McLemore also expands on character using age and gender, which can be seen in Nick and even more so in Gatsby. I will refer to The Great Gatsby’s character as Gatsby and Self-Made Boys’ as Jay for the rest of this paragraph. He remains a wealthy white man in both novels, though Jay has added context of his time spent in war being when he was underage, whereas Gatsby was likely an adult or closer to adulthood. Jay likely became a soldier so young in order to prove his manliness, since he is transgender in this story. It would make sense for him to feel he has to earn his right to manhood by serving his country, though it is a ridiculous idea in reality. Gatsby is cis, so he does not feel the need to earn his manhood in the same way Jay does, though he likely still feels like he needs to earn it in the way many cis men do due to toxic masculinity. Jay’s need is also accentuated by his being gay– gay men are often put down as being “less manly” for their attractions, as if manliness is some pinnacle that must be aspired to. It is an idea rooted in misogyny, and we see this clearly expressed in Self-Made Boys when Tom repeatedly and relentlessly makes fun of Gatsby for wearing pink, although in reality it would have been relatively normal at the time, it is written to make Tom’s homophobia clear to the modern readers. Jay’s relation to the themes of the original Gatsby are perhaps the most obvious of the primary cast; it is in the dedication pages of Self-Made Boys. Anna-Marie McLemore Selects the quote “So he invented just the sort of Jay Gatsby that a seventeen-year-old boy would be likely to invent.”, accredited to F. Scott Fitzgerald. McLemore takes the existing theme of Gatsby’s need to reinvent himself to appeal to Daisy and extends it to Jay’s core, to a history past Daisy, by making it so that he reinvents himself not due to Daisy but for his own sake. He becomes much more of a believable person in this way, while maintaining his whimsical, distant factor through his spontaneity, love for art, and romantic disposition.

Both The Great Gatsby’s Meyer Wolfsheim and Self-Made Boys’s Martha Wolf serve to explain to Nick (and thus the reader) details of Gatsby’s past that they have learned from their long-lasting business relationships with him, giving us insight to his character that we would not otherwise have due to Gatsby’s closed-off nature. Both novels feature a scene of the Wolf/shiem explaining to Nick that Gatsby was essentially “nothing” before they started doing business together. Wolfshiem, for example, says the following to Nick.

“I raised him up out of nothing, right out of the gutter. I saw right away he was a fine-appearing, gentlemanly young man, and when he told me he was at Oggsford I knew I could use him good. I got him to join the American Legion and he used to stand high there. Right off he did some work for a client of mine up to Albany. We were so thick like that in everything”—he held up two bulbous fingers—”always together.”

Wolfshiem is fond of Gatsby, and when Nick is trying to get him to attend Gatsby’s funeral he calls him Gatsby’s “closest friend”. They have a good business relationship, and Wolfshiem saw potential in Gatsby when they first met. He acts as a sort of sponsor for Gatsby, likely being the one who tells Gatsby who to get into contact with to make profits selling alcohol. They are close, for sure, but due to the nature of how The Great Gatsby is written, we don’t hear anything personal from them. The detached nature in which it is written, so we can focus on the characters as concepts rather than individuals, prevents us from attaching to their relationships in a personal way. In Self-Made Boys, Martha has a similar conversation with Nick about Gatsby’s humbler origins while they are driving. She reveals that Gatsby had been working in the Ash Heaps as a breaker boy, which is why his fingerprints have been burned away, and that Gatsby had purposefully sought her out, having heard of her ability as a sommelier and knowing her talent could be useful for selling high quality wine to the rich. Martha compliments Gatsby’s business savvy, same as Wolfshiem does; they both recognize his worth from early on.

He was eating a lot of his meals at the speakeasies,” Martha said.

“How could he afford that?” I asked.

“You can eat well in those places for below cost, because the real money’s in the liquor,” Martha said. “But if you’re going to eat that way, you have to do it fast before they realize you’re not drinking. He rotated where he went, which was smart of him, because a boy with soot stains on his clothes tended to be remembered.”

Self-Made Boys, however, is written in a more character-centric style, and we are often treated to spiels of the characters’ feelings and thoughts on each other in a way that we are not in The Great Gatsby. Martha and Wolfshiem both have strong relationships with their respective versions of Gatsby, but Martha’s connection feels more personal because we are more familiar with Martha’s own struggles in this novel. Although the relationship is the same, it is recontextualized by knowing that both she and Gatsby are queer, and they can provide each other a sort of alibi, should anything go wrong. As Martha says: “That’s something I liked about Jay right away. He doesn’t think anyone owes him an explanation.”. In the end of the novel, Martha does end up providing this sort of alibi to Gatsby so that he can move away from New York after faking his death and live happily with Nick.

The take-away is that by varying the races, genders, and sexualities of an existing cast of characters from their original form, they are given new context from which to view their world, consequently making them more three-dimensional, as well as showing us a new perspective in an old story. We see this with Nick, who although he is the narrator in both The Great Gatsby and Self-Made Boys, shows us two separate perspectives: those of a White man and a Latino trans man respectively. These variations in a re-write also allow for new audiences to connect with the story, giving it longevity through widening its readerbase. Self-Made Boys, for example, appeals to queer and POC readers, as people prefer to read stories in which they can find themselves represented.

Paper Three “Responsibility of the Artist”

Creative responsibility is a responsibility to consider the impact that one’s creative work will have on its viewers. This means to be aware of political, moral, and social stances that your work is making, and how well they are getting across. Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby adapts its novel through a lens that more closely resonates with its modern audiences. It does not show what is strictly historical and real- this is a boon to its creative direction, but further exacerbates the already wide-spread misunderstanding of what the 1920s were actually like. Is this a failure on Luhrmann’s part, or on the audience’s part?

Luhrmann’s Gatsby takes many liberties with its depiction of the 1920s, and each of these liberties is a carefully made decision which supports the kind of world Luhrmann wanted to create. It is, in a way, a modern-day version of The Great Gatsby. Although the movie itself takes place in the early to mid 1920s, the music, relationships, clothing, and even framing reflect the 2010s. By displaying the world of the 1920s how he did, Luhrmann may have inadvertently led some viewers to believe that they were like that in actuality. This is no fault of his, or the designers, and in fact points to a very successful job, since they managed to make the absurdities of their world believable to an audience. The complication comes when audiences aren’t simply transported into a fictional world, but taking it at face value as a one to one reflection of reality. Take this quote from Kelsey Egan’s “Film Production Design: Case Study of The Great Gatsby”: “Outstanding production design allows viewers to feel like they were undergoing these events. It allows an audience to relive history.” So, the production of Luhrmann’s film is certainly very effective. They are able to place objects such as inflatable zebras into scenes without much question, as it simply fits the world that has been created. They are aware of what they can pull off, what they can’t, and how to use that to cultivate the necessary energy for each scene. This is not a failure, but in fact an incredible success.

The audience, however, may not stop to consider that the carefully created dream-like feeling of the party scenes, for example, are commentary within themselves. The parties in Luhrmann’s film are a fantastic adaptation of those in the book; they are over the top, unbelievable, gaudy spectacles. The thing is, I’m not convinced that a large portion of the audience recognizes this as commentary. There is a widespread misunderstanding about the 1920s that has been very persistent for a long time, being that it was a time purely of partying and sin. While social standards did loosen up during the era, it was a direct reaction to the horrors of the first world war. Young people lost faith in the older generation, blaming them for the war, and there was a sweeping rebellion, of sorts. That’s why the boyish, boxy styles were popular for women of the time: they presented someone as young and against the older generation’s ways. The parties in the original novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald reflect this; they are hosted by Gatsby, who is desperately trying to grasp at a life he lost to the war. They allow him to escape, often literally, as he hides away in large crowds of smiling, drunk people. They are not meant to be yearned for, necessarily, but to be seen as they are: a coping mechanism. Luhrmann doesn’t shy away from this aspect, making Gatsby very awkward outside of the parties, making frequent cut-aways during them, making them by far the brightest, most eye-catching part of the film. The way they are cut, shot, and lit are disorienting. There is so much happening so quickly that it is difficult to focus on any one thing in particular, which would also be the case for the actual attendees. It’s a distraction, and one that seems to have worked almost too well on the audience. Think of any time you may have heard people speaking of The Great Gatsby in passing. I am sure that the parties come up nearly every time, if not every single time. There are many who wish to recreate these parties, disregarding the context for which they exist. To put it short, the audience doesn’t seem to be interested in dissecting why the parties are their favorite part of the movie. It is the least oppressive part. It is the part that lets you relax, that lets you take some reprieve from the palpable anxieties throughout the rest of the film. We are no better than the attendees. Does the same go for Luhrmann himself, or even the production team?

Equipped with my stance on why the film does what it does, we can move forward with how. Each character in the film has a distinct fashion sense, varying in both historical accuracy and individual personality. In any production, the costume designer’s job should be to uplift the character’s traits by representing them physically, without overpowering the other elements of the production. This is done interestingly in Luhrmann’s film. The personalities of the female characters certainly come across, each equipped with their own unique style of dress. Daisy opts for the more typical silhouette of the era, with shorter flowing dresses and glittery accessories. Jordan wears longer, more elegant clothing, which communicates to the audience that she is more confident and mature. Myrtle is a walking fashion disaster. She equips herself in 1950s style clothing, garishly bright colors, and many patterns. This communicates to us that she is not only out of style, but trying to be the center of attention.

I take issue with the costume design of this film. A quote from Alice Jurow, who is the administrator of The Art Deco Society of California, interviewed by Lisa Hix for CW magazine:

“People would be startled and disturbed if anybody actually did real 1922 fashion in the production of ‘Great Gatsby.’ It’s just not how we picture those characters.” Jurow is arguing that the inaccuracy of the costumes is necessary in order to communicate who the characters are effectively to a modern audience. I disagree with this stance wholeheartedly, and think it discredits the audience’s ability to understand basic information. Here’s a handy graphic from Bloshka depicting women’s fashion from 1910 to 1919.

Now take a look at this graphic depicting 1920s styles from Colorful Cashmere.

Although the average audience member may not be so intimately familiar with historical fashion as to detect minor differences, say, between 1910 and 1914, the difference in modernity is still incredibly obvious between the fashions of pre and post WW1 (1914). Notably, the revealing of arms and legs as time goes on. This is a basic visual cue that any person could catch onto, and not giving this basic faith to the audience would severely limit what can be done by the designers. Myrtle, for example, is described as being in her mid-thirties in the novel. The novel takes place in the summer of 1922, when women’s dresses are just above the ankle and their sleeves are typically about elbow-length. If we want to show that Myrtle has an outdated fashion sense, as a visual indicator of her older age and lower class, we would only have to bump her style back by a few years in order for the contrast between her and the other female characters to become clear. That’s the beauty of fashion in such a drastically evolving era of history: the differences are not minute. This is a real fact of history that should be harnessed to enhance the storytelling, not ignored in favor of coddling the audience.

The other part of the argument in favor of the film’s costumes is that because in the 20s, these shorter skirts were quite scandalous, we must find a visual equivalent to get it across to a modern audience that these women are attractive and fashionable. I disagree with this, as well. The reason that these changes in style were scandalous wasn’t so much to do with showing too much off, but rather what was being shown off. The turn away from accentuating waistlines and busts, as was popular pre-1914, was something of a feminist movement. The women who choose to don these loose-hanging dresses which show off their arms and legs are doing so because they are rejecting showing off their “womanly assets”, as it were. They are taking matters into their own hands, giving themselves more freedom with their clothing. That’s what made it a “sexy” look at the time- not that their legs were out, but that their legs being out meant that they were more open-minded and fun-loving. My argument here is that the style of the 2010s did the same as the 1910s, leaning into an accentuation of hips, waists, and busts. It would then be more of an analog to keep the more boyish styles of the 1920s, because it shows a deviation from what is typical, which is what the women of the time were actually going for. The men’s fashion in the movie is overall lacklustre, basic, and uninspired. They stick to simple American style suits for every main male character, and the most interesting outfit we get for them is Tom’s polo regalia. Where the designer, Catherine Martin, went too far away from reality with the women’s costuming, she stayed too close to reality with the men’s.

Ultimately, I believe there should simply be a happier medium found. There is no problem with taking creative liberties to make an interesting product; nothing in this movie is 1:1 accurate, and it shouldn’t have to be. There seems to have been a fundamental misunderstanding of exactly why women were dressing like they were in the 1920s, however, that leaves a sour taste in my mouth as a viewer and costume enthusiast. There are many virtues to the actual fashion of the twenties, and discarding these beautiful garments in favor of backless dresses and busty corsets is an unbelievable shame. Women were being rebellious, not appealing to men’s taste. The costumes in Luhrmann’s film step all over this idea- shoving them right back into the male gaze with the excuse that that’s what it was historically equivalent to. A shame, given the costume designer herself was a woman.

Interestingly, the set design followed much clearer rules. Catherine Martin quotes: “Baz made a rule that we were able to use any influences or references from 1922 through 1929. His rationale was that the book was set in ’22, published in ’25, and foreshadowed the crash of ’29”. A clear time period is provided for the set designers to work within the limits of. The set design of Luhrmann’s Gatsby is absolutely phenomenal- a true spectacle to reflect Gatsby’s own flair for the dramatic. It is completely over the top, gaudy, and glittery, everything you would think Gatsby to be. It is both accurate (to a point) and interesting. Gatsby lives in a ridiculous Disney castle of a home, looming at the top of the hill, bathed in golden light from within. The showiness of the sets never seems to overtake the characters, only exemplifying Gatsby’s oppressive dramatics. Take when he moves the flowers into Nick’s cabin for his meeting with Daisy. It is a physical manifestation of how Gatsby is inserting himself into Nick’s dull life- overwhelming his small space with flowers and workers and his own anxieties about whether it will be good enough for Daisy. There is another quote from Catherine Martin, “My aim is to express the true nature of the period through an electric combination of things that have a real point of reference.” I would say this is absolutely wonderfully done with the sets, and I simply must speak its praises. Its success even further accentuated my disappointment with the costumes while I was watching the film. If playing with the rules of accuracy was so successful in the backgrounds, why couldn’t it be as lovely in the foreground?

There is a quote from Walford, co-founder of the Fashion History Museum, in the CW article I have been referencing that sums up my feelings perfectly: “Luhrmann tried to make the story relevant by interpreting the 1920s in a way that would appeal to today’s audience. To that end, I think Luhrmann, and everyone associated with the film, did a splendid job.” Walfords takes in this article overall are absolutely fantastic, and I agree with him wholeheartedly throughout. I do not believe this is a bad film. I believe it is a bit of a mess, and that the audience has done a poor job interpreting it, and that the costumes leave much to be desired; but it is a fascinating watch. I suppose in that way it’s a perfect adaptation of The Great Gatsby, leaving you hungry to understand why it is how it is, wanting to pick the creator’s minds. Toeing the line between reality and fiction is difficult, and a reason why good historical fiction is so satisfying. Luhrmann is an incredible director, and I do not think that this was the novel for him to adapt, although it was fascinating.

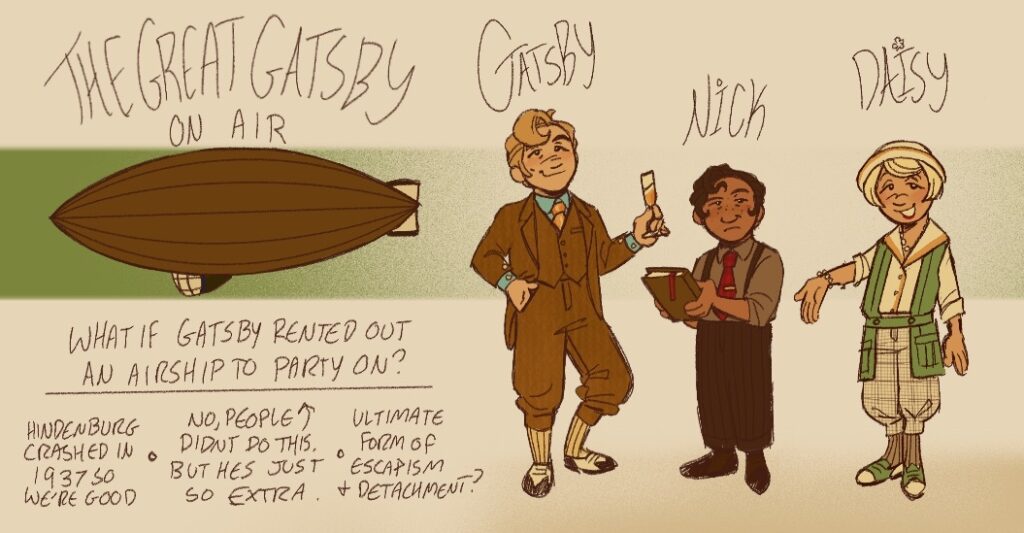

For my multimodal media project, I decided to draw an imagining of an alternate version of TGG where Gatsby rents out an airship to party on. Simply because I love airships, and they were around during the era.

I’m heavily influenced by the versions of Jay, Nick, and Daisy in Self-Made Boys. So especially with regards to Nick and Daisy, they’re very much so based on how they are written by Anna-Marie McLemore.

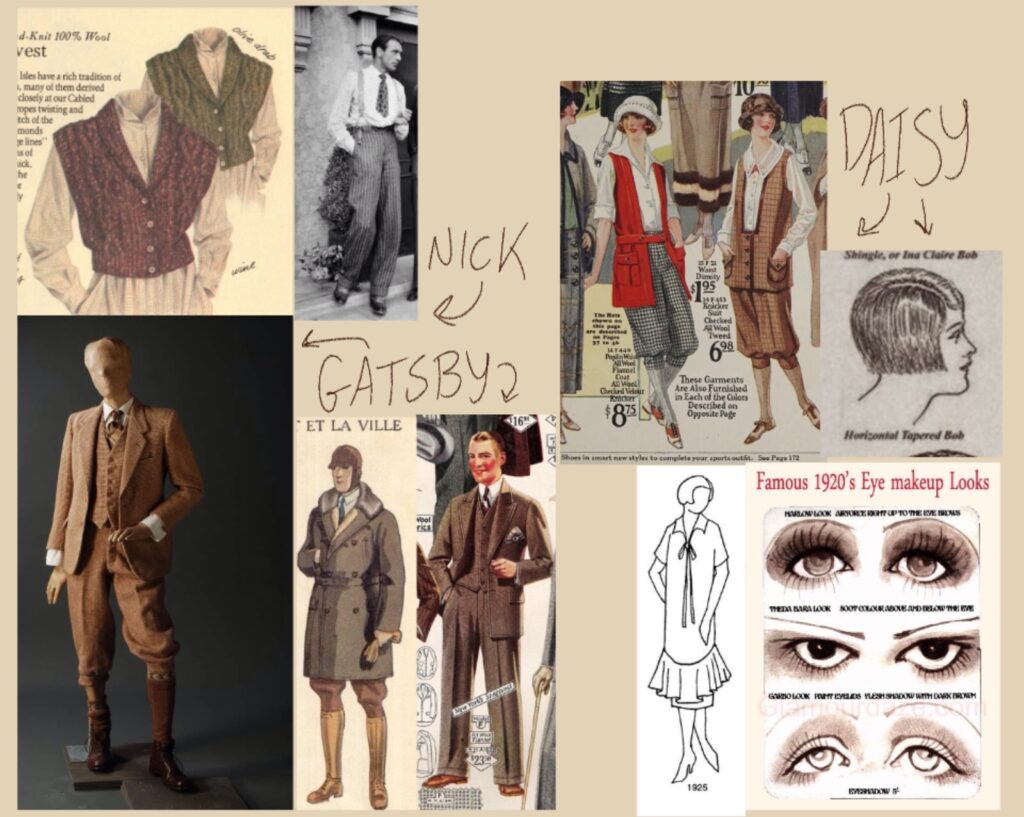

I’m also including the quick little fashion reference guide I put together for myself! I found all the images with cursory Pinterest searches. Most are simply from old fashion catalogs.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. The Project Gutenberg eBook of

The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott

Fitzgerald. eBook #64317. Project Gutenberg, January 17, 2021, online

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/64317/64317-h/64317-h.htm

Excerpt of a Review from The 21st Century Great Gatsby course website

Mencken, H.L. “Review of The Great Gatsby from the Chicago Tribune.”

Mintler, Catherine. The Great

Gatsby: 21st Century Great Gatsby. Online. Access Date.

https://crmintler.com/21CTGG/

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. “Letter to Maxwell Perkins.” July 2022. Online. Canvas.

Mintler, Catherine. 21st

Century Great Gatsby. Expo 1213-001/002. 5 January 2025.

https://canvas.ou.edu/courses/290048/assignments/2232667

Egan, Kelsey. “Film Production Design: Case Study of The Great Gatsby.” Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications 5.1 (2014). <http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=968>

Hix, Lisa. 2013. “Did Hollywood Give The 1920S A Boob Job? ‘Gatsby’ Costume

Designer Tells All | Collectors Weekly”. Collectorsweekly.Com.

https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/did-hollywood-give-the-1920s-a-boob-job/.

Luhrmann, Baz. 2013. The Great Gatsby. Film. Warner Bros. Pictures.

Rohrkemper, John. “The Allusive Past: Historical Perspective in The Great Gatsby.” College literature. 12.2 153–162. Print.